As you may have discerned from the flurry of recent (but paradoxically still dated) posts on a trip back in September 2022, we’re trying to get our act together and get WolfeStreetTravel.com up to date. (@wolfestreetravel on Instagram is always current, for what it’s worth, inasmuch as we post there in real time during our travels.)

With that context, this post mercifully is our last one on the Cappadocia leg of the Turkey / Greece trip, before we pivot to the trip’s second leg in Greece. (We’re trying to address the entirety of the remainder of this trip before we take off soon for another long jaunt in Europe, when where posting will once again cease for a while. Upon our return we’ll get to the other four backlogged trips (which will have grown to five by then).)

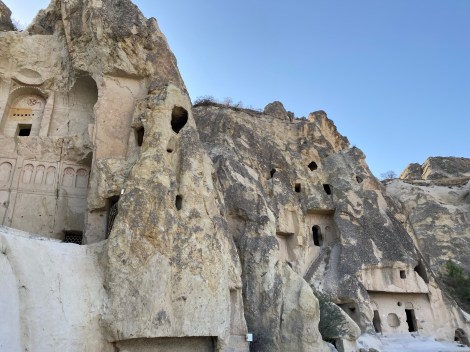

Our flight departing Cappadocia for Athens took off in the afternoon, so we spent the morning of our last day wandering through the Göreme Cave Monastery complex down the road from our base town. Founded in the 4th century on the instruction of Saint Basil of Caesarea, this complex of monasteries, nunneries, churches, and chapels existed for a thousand years. It was far and away the coolest of the troglodyte settlements we visited in Cappadocia for reasons that will immediately become apparent.

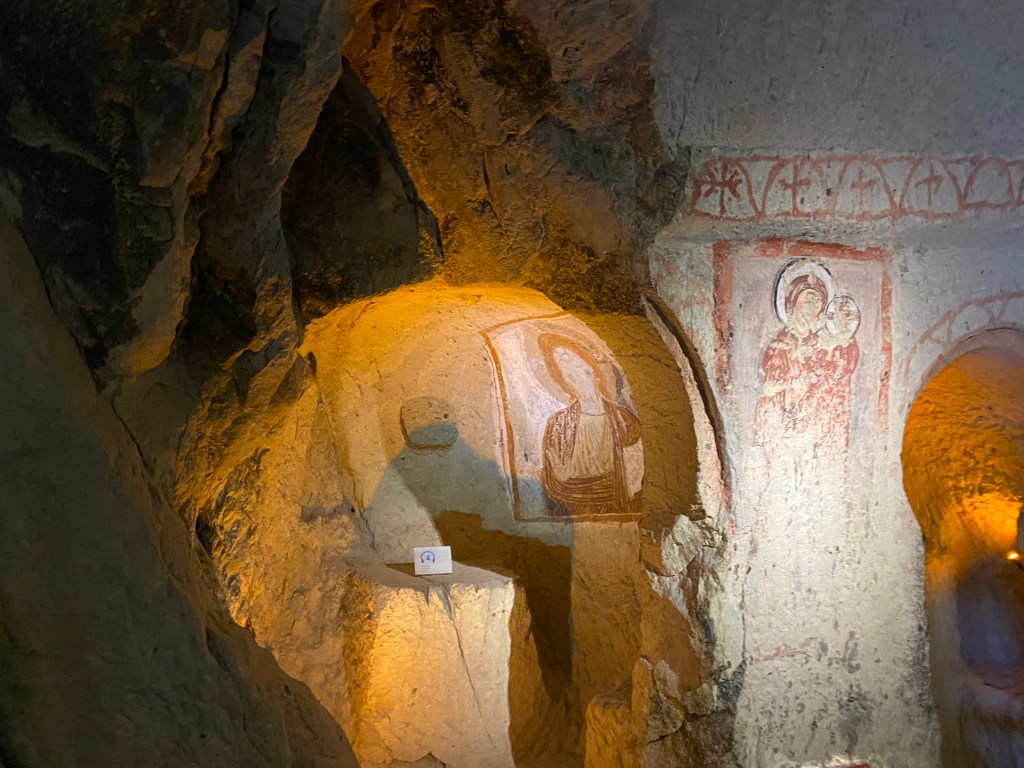

There were so many structures here to appreciate – predominantly cave churches – that it became a little overwhelming to take everything in. One delineation of cave church decoration helped us contextualize things, though: did the cave feature rudimentary symbols and patterns (representative of the iconoclastic era) or were the walls and ceiling drenched in richly illustrated frescos of saints and other religious themes that characterized the post-iconoclastic era? The former represented an era in the 8th and 9th centuries, when while the Byzantine church found religious images to be idolatrous, and the latter were created later, when the iconophiles won out in arguing that these depictions were acceptable – and even desirable – for enlightening the illiterate (similar to western European medieval church frescos and, later, stained windows).

The first church we encountered (which we forgot to identify for later review) exemplified the iconoclastic style:

Just red ochre symbols and patterns:

But that was just the beginning.

St. Barbara

The iconoclastic style also adorned the raw rock walls of this much more ornately decorated cave church.

Decorated almost entirely in red ochre geometric designs and religious symbols, every soffit, cornice, and pendentive (triangles supporting the domes) are embellished.

These mostly are manifested as triangles, checks, lightning-bolt-looking things, and Maltese crosses.

Oh – and there’s a boxing pheasant on one end of a barrel vault in St. Barbara? Or something? Definitely the most amusing yet mysterious of the images.

Below the boxing pheasant, of course, is a very post-iconoclastic images of Saint George and Saint Theodore. Not sure what to say about this juxtaposition.

Whether iconoclastic symbols or lush paintings, we found these churches to be so compelling because of the incredible age of the art and the palpable presence of everything so present with you, where you could reach out and touch a symbol that a monk applied to an arch more than a millennium ago.

Our hometown is old and, with a founding date of 1749, we pass by centuries’ old buildings and artifacts every day. Hell, our house is 100 years old. But St. Barbara dates to ~1100 (don’t ask how to reconcile how this falls after the iconoclast era), and being so casually close to religious art that old and yet so accessible elicited a pretty palpably powerful feeling of awe.

Dark Church

At the opposite end of the spectrum is the foreboding-sounding “Dark Church” (so named not for serving as the unholy site of arcane acts and an upside down cross, but because the only illumination of the church results from a small window in the church’s narthex). As a result of this paucity of sunlight, the paintings inside have been remarkably preserved.

The Dark Church definitely had the most ornate exterior. While the other churches’ exteriors were simply the rocky hillside, the Dark Church exterior featured a carved façade, including a series of keyhole niches with Greek crosses.

The entrance:

Very different interior from the iconoclastic churches!

The central dome features the very Byzantine Christ Pantocrator image and the four archangels (Gabriel, Michael, Raphael, and Azrael) occupy the four small domes surrounding it.

These paintings all date from the latter half of the 11th century.

Amazing that this work from 1100 years ago still remains, unaltered, to appreciate:

Snake Church

Although the Snake Church clearly demonstrates full illustrations representative of the post-iconoclasm period, it nonetheless also represents something of a transition in its liberal use of simple drawings and symbols, including on the outside of the cave church:

“The mural painting on the left has five figures—St. Onesimus standing in a red robe, Saints George and Theodore on horseback, and Saints Constantine and Helen holding the True Cross.

The figure nearest the door is St. Onesimus, mentioned in the New Testament letter Philemon. He was a first-century slave who escaped from his master in Colossae (near modern Pamukale/Denizli). As Onesimus was hiding in Rome, he encountered the apostle Paul and became a Christian. To restore their relationship, Paul sent Onesimus back to his master Philemon (who happened to be Paul’s friend), requesting forgiveness. According to church tradition, Onesimus was later martyred, as symbolized by the white cross that he holds.” (From here.)

Inside, along one side of the nave, can be found the reason behind the name: an image of Saint George and Saint Theodore slaying a dragon, here depicted as a snake (you can make out the scaly body on the right bottom and the tail on the left, but there’s not a lot left to make out of the head):

More of the mix of iconoclastic and post-iconoclastic imagery on the barrel-vaulted ceiling of the nave.

At the far end, a rudimentary apse with Jebus on the lunette above:

And a cool checkerboard pattern above the entrance:

St. Basil’s Chapel

“The left wall has two panel icons. The tall image on the left is St. Basil the Great, the famed bishop of Caesarea (d. 379 AD) who defended Nicene Orthodoxy and pioneered Byzantine monasticism.

The larger square image is St. Theodore on a red horse, spearing a snake. His clothing mimics Roman military attire, but has subtle Persian designs. Theodore Stratelates (“The General”) was martyred in 319 AD in Pontus (northern Turkey).” (From here.)

“The large, square icon is St. George riding a white horse. He was a Roman officer from Cappadocia who died in the early 300’s, in Nicomedia (the first capital of the Eastern Roman Empire, modern Izmit).” (From here.)

The coolest aspects of St. Basil’s though had to be the tombs. In a cave. (Cave graves, if you will.) The acrosolium (arched recess with grave) below was part of the original church design:

However, twelve more were later carved into the stone floor of the church – adults in the middle and infants on the side:

The occupants of the cave graves are unknown. This one was reminiscent of the crystal skeleton in the ATM cave in Belize.

On our way out, a familiar sight over the valley:

Cappadocia complete! From here, we hightailed it back to our place in Göreme, grabbed our luggage, and headed to the airport – and thence to the Greek Cyclades island of Paros.