When we decided to buy one-way plane tickets to Europe for our first prolonged foray to celebrate the second of the two retirements, we knew we wanted to return to Italy as a start, but the destinations within Italia, and certainly beyond, weren’t intuitive at the outset. We know we’d be in Tuscany because of the Brandts; we knew we wanted to visit the Amalfi Coast for the first time; we knew we wanted to spend time in Sicily; one of us knew he wanted to check out Herculaneum; the other knew she wanted to visit Portofino. But some locations we were familiar with, but were not on our list, nonetheless ended up on our itinerary simply because they were a convenient stopping point between one target and the next (like Orvieto).

Then, there’s Matera. Not only did Matera not rate a “let’s make sure we go there” spot on the aspirational list – it wasn’t even a town that was known to us. Instead, we stumbled upon this gem during trip planning.

As part of our planning process, the Chief Adventure Officer creates a Google Map with potential places of interest and – overlaid on top – hotels that are part of our favored collections (Relais & Chateau, Small Luxury Hotels, Design Hotels, Rosewood, and some others). If a location highlighted on travel sites or on Instagram looks appealing AND that is home to hotels from one or more of our collections, we figure it really is worth seeing, since boutique hotels wouldn’t be in some shit town. When we overlaid Design Hotels on the Italy map, the town of Matera was suddenly on our radar. And it was between the Amalfi Coast and Bari, where we’d be on a plane headed for Sardinia. So we started researching this new discovery.

Definitely the right choice

“Before its integration into the modern Italian state, the city of Matera had experienced the rule of the Romans, Lombards, Arabs, Byzantine Greeks, Swabians, Angevins, Aragonese, and Bourbons. Although scholars continue to debate the date the dwellings were first occupied in Matera, and the continuity of their subsequent occupation, the area of what is now Matera is believed to have been settled since the Palaeolithic (tenth millennium BC). This makes it potentially one of the oldest continually inhabited settlements in the world.” (From here.) (And we thought Cadiz‘ history was epic.)

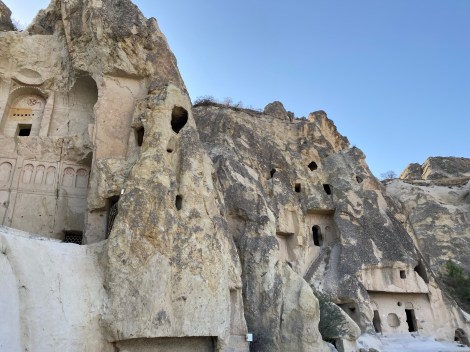

Matera’s Sassi—neighborhoods of cave dwellings carved into soft limestone—provided shelter, water collection, and natural insulation. Over centuries, however, population growth and abandonment by the state turned this ingenious landscape into one of extreme deprivation: families lived packed into single-room caves, often sharing the space with livestock, with little ventilation, no running water, no sewage, and widespread disease. By the 19th and early 20th centuries, a stark social divide had formed – Matera’s poorest residents were confined to the Sassi while wealthier families, professionals, and institutions moved up to the piano, the healthier, flatter upper city with light, air, and services. This physical separation mirrored a deeper economic and social gulf, making the Sassi a powerful symbol of southern Italy’s poverty and exclusion. Only after World War II did national attention and government intervention begin to dismantle these conditions, setting Matera on a long path from neglect to preservation.

Carlo Levi, a fiercely anti-fascist doctor, was exiled by Mussolini’s regime to the Basilicata region in 1935 and he described Matera as proof that Italy was actually two civilizations: a modern, northern one and a forgotten, quasi-prehistoric southern one. “Inside those black caves that had walls made of soil, I could see the beds, the poor furnishings, the clothes hanging. Dogs, sheep, goats, and pigs were lying down on the floor. Typically, every family owns just one of those caves as a house, and they sleep all together: men, women, children, animals. There was an infinite number of children. . . sitting in the baking sun, on the doorsteps of their houses, into the dirt, their eyes were half closed and their eyelids red and swollen. This was due to trachoma. I knew that here people suffered from it: but seeing its effects in filth and in extreme poverty it is a different thing. . . it seemed to be in a city stricken by the plague.”

Despite the have and have not history of Matera and the primitive conditions of the sassi, this place has come into its own. Freaking amazing warren of troglodyte homes and alleys built into the soft limestone of the valley. It was like an inverted Gordes – picturesque and full of character.

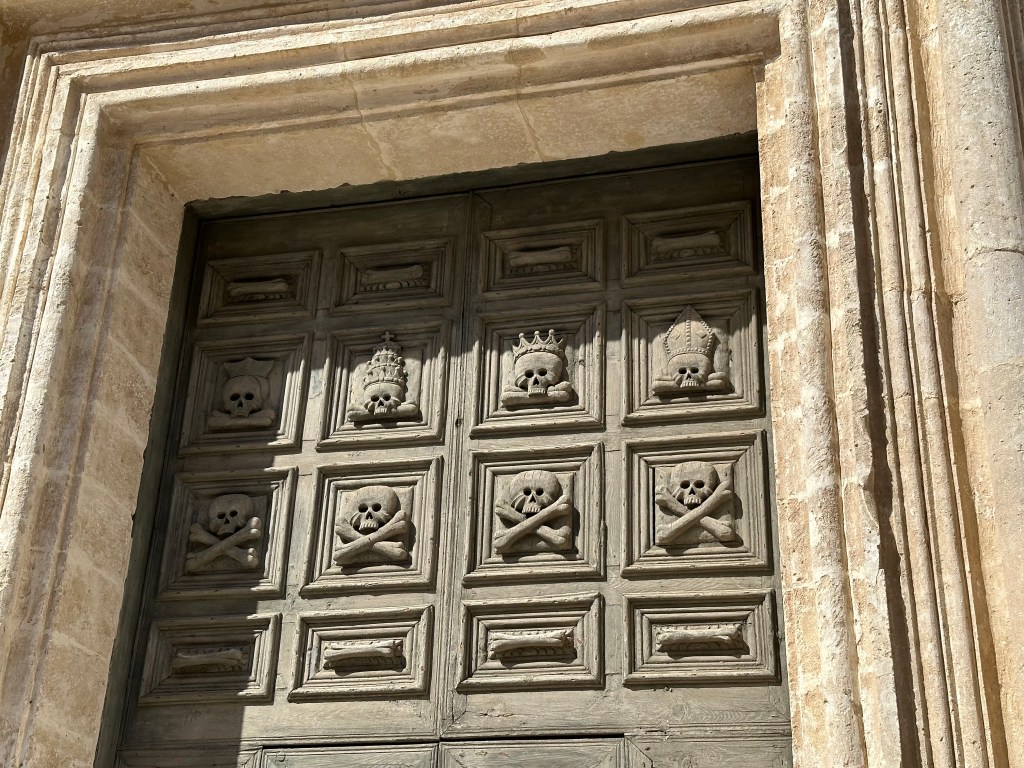

At the edge of the sassi lies Chiesa del Purgatorio (Church of Purgatory).

The church was built in the 18th century and embodies baroque church architecture (which we’d see plenty of a couple of weeks later in central Sicily), but that’s not why it’s notable.

It’s notable for it’s embellishments everywhere that serve as reminders of mortality (memento mori),

and the need to pray for souls in pergatory.

The door is the coolest part.

“It’s decorated with four skulls of nobles and clergymen and just under these, four skulls representing common people, with four more on the side of the entrance.” (From here.)

But the skulls-on-a-plinth are a good look, too:

At the other end of town, a different religious institution: The Convent of Saint Augustine.

A relative latecomer, having been founded in 1591, it’s still a pretty impressive and monolithic structure, perched on a cliff at the very edge of the sassi.

And in its shadow, a humble rupestrian church (new term to us! we would have characterized this cave church as troglodyte [like we did in this post from Cappadocia], but rupestrian works too).

Founded in the 10th century, San Nicola Dei Greci originated as a Greek Orthodox church (see Byzantine Greek rule reference above

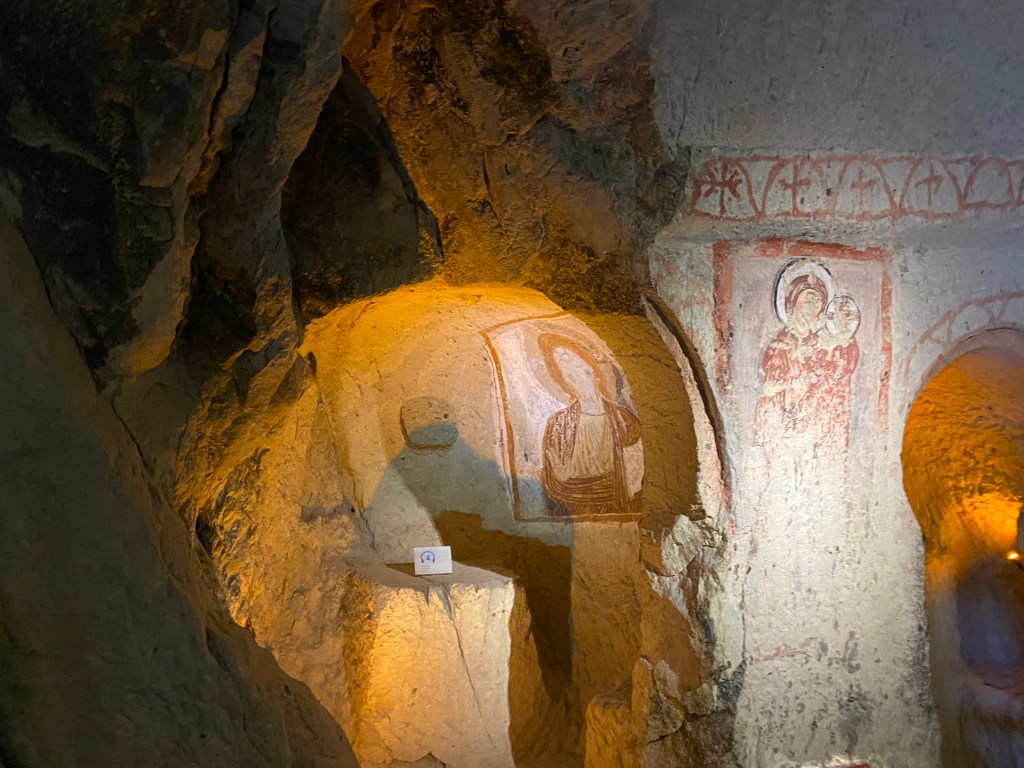

The triptych fresco depicting Saint Nicolas, Saint Barbara, and Saint Pantaleon (not to be confused with Saint Pantaloons, patron saint of trousers and culottes) dates from the 12th to 13th centuries:

The church was used as a burial site during the middle ages and there are two graves in the floor of the right aisle (similar to not only the Cappadocia cave churches but also the Abbeye de Montmajour in Provence).

This fresco dates from the 14th century:

Check this shit out! This is why Europe is so incredible; we were just wandering about a troglodyte church with 800-year-old frescos adorning its walls with the same casualness as walking into a Starbucks.

With that under our belt, we head out in search of some lunch.

Outside the sassi in the Piazza San Pietro Caveoso with the cathedral’s bell tower looming over town:

Chiesa di San Pietro Caveoso (The Church of Saints Peter and Paul, the latter of whom apparently went the way of Hamilton of Booz Allen Hamilton in the church name):

The original church dates to 1218, but the current appearance reflects a comprehensive overhaul in the 17th century. Picturesque, and with a well-positioned plaza facing the sassi (as noted above), it’s still not quite as cool as the rupestrian church above it.

“Dating to the 8th century, when it was built as the Benedictine Order’s first foothold in Matera, this cliff-face church has a number of 13th-century frescoes, including an unusual breastfeeding Madonna. The church originally comprised three aisles, with two later adapted as dwellings.” (From here.) We got to see the inside, which did indeed have multiple frescoes, as with the other rupestrian church, but no cameras were allowed in this one or in another one we popped into inside the sassi area.

A view of the other end of the sassi facing the valley:

What’s a town to do for a dump truck if most of the roads are narrow, up-and-down alleyways? This:

Also, a picture that captures the recycling specificity that uniquely characterizes Italy and no other country, European or otherwise, that we’ve visited:

We first encountered this during our second visit to Siena, and then at our AirB&B in Portofino. You’ve got to separate glass from metal from paper from food waste and from general refuse (not that there’s much left after all of that sorting). Which raises questions like, where do we deposit the paper coffee filter (paper) filled with coffee grounds (food waste)? Or this burnt out light bulb comprised of brass (metal) and glass (um, glass)? These are the challenges WolfeStreetTravel must cope with!

Heading out for aperitivos high up in the sassi and then dinner on our last night:

One of the best dinners of the visits, actually.

Pretty awesome conversion of a troglodyte church into a wine bar:

And some good freakin’ pesto:

Sassi day time:

Sassi night time:

The next morning, we retrieved our car for the drive to the Bari airport. In what appears to be a self-storage warehouse:

But behold! A bunch of tight garages for sassi residents who can’t bring their cars (for obvious reasons) into town:

And the weirdest car to date: a dr, which is an Italian car brand that uses Chinese auto bodies. Go figure. Regardless, this was our last day with it.

On to Sardinia!